In this Communications of the ACM column we discuss whether research conferences in computer science are too close to new members trying to join the ranks, especially when these new members try to enter the community “alone” (i.e. not publishing together with already established members). More than trying to be provocative, our goal is to discuss potential measures to make our top conferences more inclusive. Below, the (unedited) version of the column for those that can’t go through the ACM paywall.

Introduction

Publication in top conferences is a key factor, albeit controversial [1], [2], in the dissemination of ideas and career promotion in many areas of computer science. Still, the feeling is that publishing in a top conference is something reserved to the established members in the community around it. For newcomers, this is a tough nut to crack. Indeed, when talking with fellow researchers the assumed unspoken truth is always the same: if you’re not already one of “them”, you have no chance to get “in” alone.

If this were true, it implies senior researchers wishing to change fields during their research career may have a hard time doing so. But it would have an even more dramatic impact on junior researchers: they could only access top venues by going together with their supervisor, limiting their options to make a name by themselves. Exactly the opposite of what evaluation committees typically require from candidates, who are supposed to show they are able to propose and develop valid research lines independently of their supervisor, even better if it is in a slightly different field and hence in a different community.

But, is, in fact, true that conferences are close communities or is it just a myth popularized by those that tried and failed? Is there data to back up this claim? And if so, how do we change this situation (and do we really need to change it)? Our goal is to shed some light on these issues.

Looking at the conferences data

As an experiment, we have evaluated the number of newcomer papers (research papers where all authors are new to the conference, i.e. none of the authors has ever published a paper of any kind in that same conference) of 65 conferences in 2015. The list of selected conferences corresponds to the list of international CS conferences in the CORE ranking Computer Software category, for which we were able to find available data in the DBLP dataset, the well-known online reference for computers science bibliographic information. The choice of CORE as the ranking system is simply based on its widespread use. We have analyzed the conferences using a seven-year window (i.e., an author is considered new to a conference if it has not published in that conference in the last seven years). We only count full papers in the main research track (since getting short papers, posters, demos, etc. is typically easier but it barely counts towards promotion). Manual curation of the DBLP data was required to properly classify the papers since proceedings do not always explicitly include the track / category information.

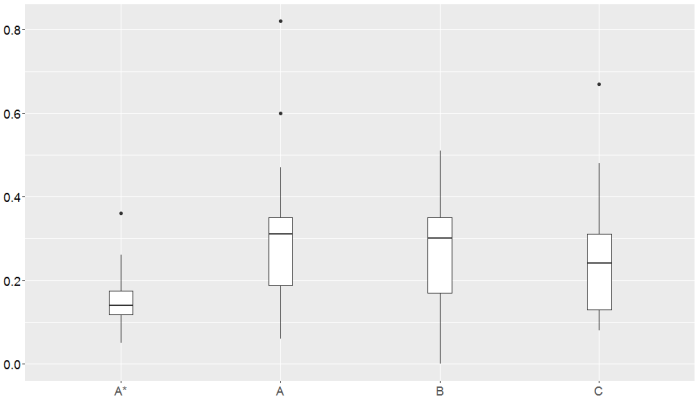

Figure 1 summarizes the results. Conferences are grouped according to its ranking (A* being the top one). Most conferences show a percentage of newcomer papers under 40 percent. This value is significantly lower in top conferences, with a median value of 14%. As specific examples, well-regarded conferences show the following values: ICSE (5%), OOPSLA (13%), ICFP (11%), RE (6%). The full data is available.

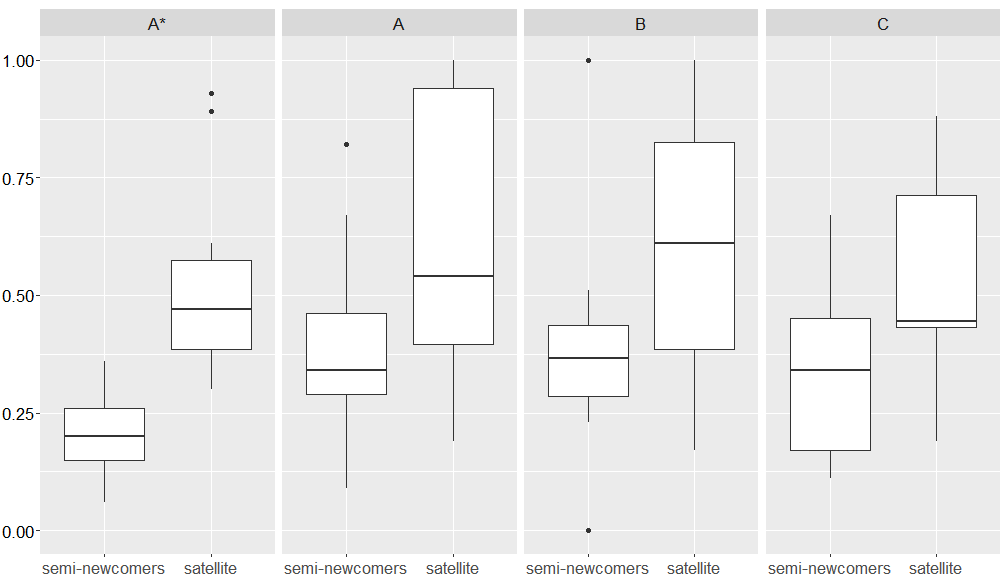

Additionally, for each conference, we have also calculated two more related metrics: semi-newcomer papers (research papers co-authored by researchers that have never published a research paper in the conference but that may have presented in the conference other kinds of works) and newcomer satellite papers (papers outside the main research track, i.e., posters, demos or papers in co-located events, co-authored by researchers that have never participated in the conference before). Figure 2 shows the results of these two metrics confirming that starting by publishing in a satellite event/track before attempting to publish in the main conference slightly increases your chances of success and that publishing in those events is feasible even for top conferences (though the level of “easiness” shows a large variance). Clearly, as expected, satellite events play a positive role in the growth of the community. Following on the previous examples, the semi-newcomer and satellite metrics for the illustrative conferences are, respectively: ICSE (15% vs. 34%), OOPSLA (19% vs. 47%), ICFP (17% vs. 37%), RE (17% vs. 32%).

Opening up conferences

We believe the data confirms CS conferences (at the very least in the area we have evaluated but we do believe results can be generalized) behave as closed communities. We are sure some readers strongly believe this is exactly how things should be and that newcomers need to first learn the community’s particular “culture” (in the widest sense of the word, including its topics of interest, preferred research methods, social behaviour, vocabulary and even writing style) either by simply attending the conference or warming-up publishing in satellite events, before being able to get their papers accepted in the main research track.

We dare to disagree and argue that the situation is getting to a point in which is worth to discuss how to change course. The overall presence of newcomers decreases over time [3]. Besides, increasing travel and economical restrictions make difficult to follow the (so far) “standard” path to enter the community, e.g. many junior researchers will not get funded just to attend a workshop. While closed communities have indeed some positive aspects (e.g. focus, heritage to build up on, sense of security, …) we believe they are now becoming too close. In our opinion, a more healthy number for conferences would be having at least 25% of newcomer papers in each edition. This would ensure a continuous influx of fresh ideas and new members in the community among other benefits of open communities such as better diversity and inclusiveness (note that junior researchers co-authoring a paper with their supervisor could be also considered new members but here we refer as new members to people really coming from outside the community and therefore bringing a fresh pair of eyes).

The main challenge in opening up conferences comes from the fact that we do not really know the reasons why these numbers are so low. Do newcomers refrain from submitting in the first place? Do they get rejected more often than established authors? If the latter, are they being fairly rejected because their papers do not follow the right structure, process or evaluation standards or is there a positive (unconscious) bias towards known community members during the review phase?

Solutions may differ depending on the root cause but we would like to suggest a few ideas we think are worth pursuing:

- Starting mentoring/shepherding programs where young researchers can pre-submit their work and get some advice (typically from former PC members) before the actual submission. There are a few conferences that have tried this but we have not seen data reporting on whether it was successful to increase the newcomers rate.

- Opening the review process. More and more conferences are adopting a double-blind review model to avoid bias but what about having open reviews (where reviewers sign the reviews and/or reviews are later released publicly)?

- Draw ideas from other domains where they may face similar problems. For instance, in the open source community, many projects struggle to attract new contributors and have come up with proposals to attract more people and keep them inside the community as soon as they attempt to submit a first contribution [4]. Examples (adapted to our field) would be to have a dedicated portal for newcomers clearly explaining how papers in the conference are evaluated, showing examples of good papers (in terms of style and structure), listing typical mistakes first submitters do based on the experience of PC members, etc.

- Identify research topics with a lower entry barrier for newcomers either because they are new topics, and therefore not many people in the community work on them or because they require less advanced skills/infrastructure.

- Decide to increase acceptance rates to have more slots available. You could even decide that a certain number of slots are reserved for newcomer papers. Sure, this goes against the traditional conference publication model but there is already a part of the community that challenge the idea that very low acceptance rates are indeed good for us.

Despite the number of works analyzing co-authorship graphs [5]–[7], newcomers metrics have been mostly ignored in previous research works. M. Biryukov et al. [8] study individual newcomer authors, B. Vasilescu et al. [9] and J.L. Cánovas et al. [3] calculate a coarse-grained newcomers value as part of a larger set of general metrics on conference communities but do not exploit the value to analyze the problematic behind it. We hope to trigger additional research and, specially, general discussions around the complex trade-offs of closing / opening up more our research communities [10] with the present work. And we should probably have the same conversation about top journals, which show symptoms of this same problem.

References

[1] M. Franceschet and Massimo, “The role of conference publications in CS,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 53, no. 12, p. 129, Dec. 2010.

[2] J. Freyne, L. Coyle, B. Smyth, and P. Cunningham, “Relative status of journal and conference publications in computer science,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 53, no. 11, p. 124, Nov. 2010.

[3] J. L. Cánovas Izquierdo, V. Cosentino, and J. Cabot, “Analysis of co-authorship graphs of CORE-ranked software conferences,” Scientometrics, vol. 109, no. 3, pp. 1665–1693, Dec. 2016.

[4] I. Steinmacher, M. A. Graciotto Silva, M. A. Gerosa, and D. F. Redmiles, “A systematic literature review on the barriers faced by newcomers to open source software projects,” Information and Software Technology, vol. 59, pp. 67–85, 2015.

[5] A. E. Hassan and R. C. Holt, “The Small World of Software Reverse Engineering,” in Working Conference on Reverse Engineering, 2004, pp. 278–283.

[6] E. Sarigöl, R. Pfitzner, I. Scholtes, A. Garas, and F. Schweitzer, “Predicting scientific success based on coauthorship networks,” EPJ Data Science, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 9, 2014.

[7] E. Yan and Y. Ding, “Discovering author impact: A PageRank perspective,” Information Processing & Management, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 125–134, 2011.

[8] M. Biryukov and C. Dong, “Analysis of computer science communities based on DBLP,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 6273 LNCS, pp. 228–235, 2010.

[9] B. Vasilescu, A. Serebrenik, T. Mens, M. G. J. van den Brand, E. Pek, M. G. J. Van Den Brand, and E. Pek, “How healthy are software engineering conferences?,” Science of Computer Programming, vol. 89, no. PART C, pp. 251–272, 2014.

[10] D. Gebert and S. Boerner, “The Open and the Closed Corporation as Conflicting forms of Organization,” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 341–359, Sep. 1999.